The results of the study, in which the Center for Child Dignity was a partner, are published in a foreign scientific publication

The article "Should I Stay or Should I Go? Relationships Between Emotion Regulation and Basic Needs Satisfaction of Parents Displaced in Ukraine and Abroad" (original title "Should I Stay or Should I Go?" Relationships Between Emotion Regulation and Basic Needs Satisfaction of Parents Displaced in Ukraine and Abroad") in the scientific journal "Education, Culture and Society" № 1_2023 283 (Journal of Education Culture and Society), which is part of the international scientometric databases. The article was based on the materials of a study that lasted for the first 3-6 months of the war. Among the authors are experts from the UCU Department of Psychology and Psychotherapy - Anastasia Shyroka, Oksana Senyk, Tetiana Zavada, Olena Vons, and Anna Kornadt from the University of Luxembourg. The UCU Center for Child Dignity became a partner in the study. We talk in more detail about the results with its co-author Anastasia Shyroka, a psychologist, associate professor of psychology and psychotherapy at the UCU Faculty of Health.

It is good news that Ukrainian research has been published in an international publication. Ms. Anastasia, please tell us how it all started.

In the first month of the full-scale invasion, there was a lot of anxiety, uncertainty, and everyone was trying to keep themselves busy by getting involved in some important activities. I thought about how I could personally be useful. I had an inner conviction, which is still relevant today, that Ukraine should have its own voice on international platforms, including in scientific journals. The suggestion of Khrystyna Shabat, head of the UCU Center for Child Dignity, to do a study was interesting because it is another way to tell the world what Ukrainian parents and children who were forced to leave their homes are going through since the beginning of the war.

It is important for us to have our own story about the experience that Ukrainian parents and their children went through during the displacement.

Yes, a story that speaks directly to the experience of Ukrainians is very important. Please tell us more about the study itself.

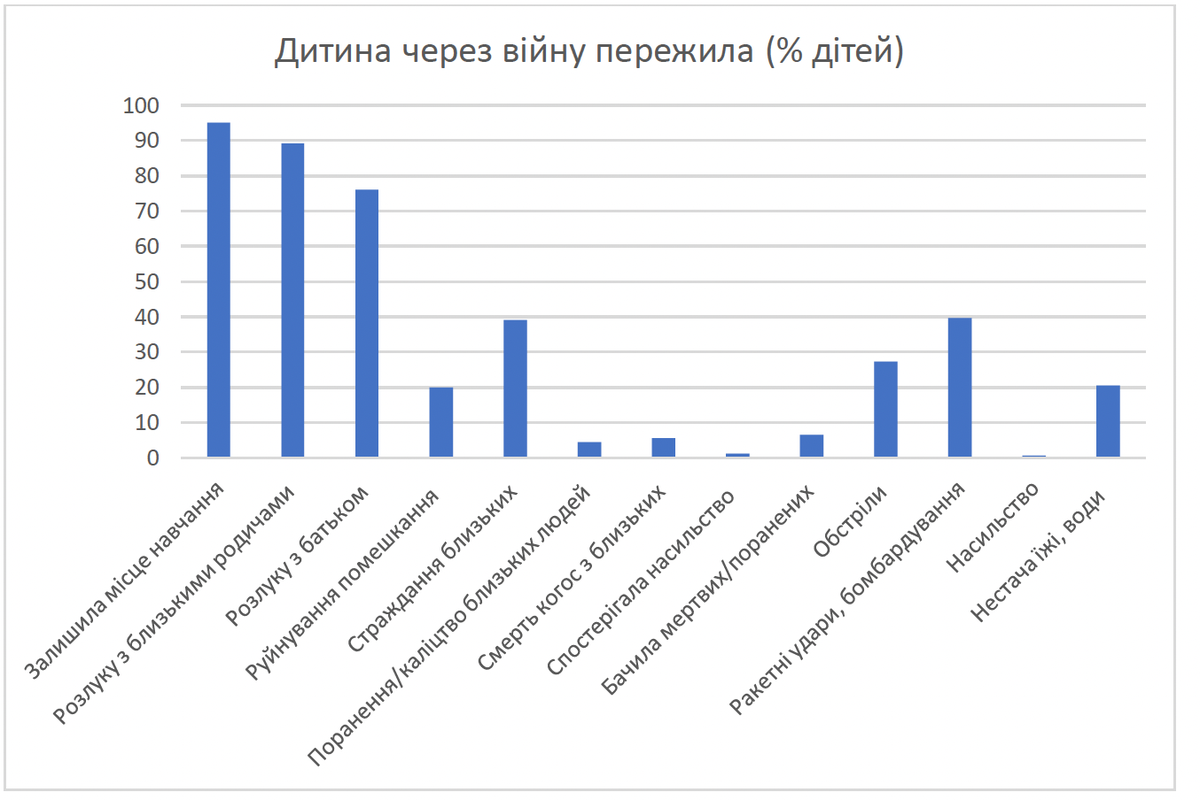

Starting from the second month of the full-scale invasion, we began to study the emotional state of parents and various mental health indicators of their children who were forced to move to safer regions of Ukraine or abroad. In particular, it turned out that 85% of the parents and children we studied had experienced 3 to 7 traumatic events related to the war. Among the most common are the loss of a place of study (friends, classmates, familiar environment) (95%), separation from relatives (90%) and from a parent (76%). About half of the children witnessed rocket attacks and bombings (40%); had close people who experienced the consequences of war (e.g., through participation in hostilities; as civilian victims, due to armed attack or lack of food, lack of medical care, etc.) (39%), one third were shelled (27%), and one in five experienced a lack of food, water, and other basic necessities due to the need to stay in shelter for a long time (21%). These figures suggest the level of traumatization of Ukrainians.

The survey questions focused on the emotional experiences of parents and the mental health of children. The survey was anonymous and confidential, and parents could refuse to participate at any time. We also offered contacts for free psychological counseling in the survey, which was important given the situation.

In the published article, we talk about the experience of parents, namely, what are their predominant ways of coping with their emotions, how well are their basic needs met, such as the need for food, housing, financial capacity, clothing and hygiene, healthcare and education for children. And also, what is the relationship between emotional regulation and the satisfaction of basic needs. First of all, we were interested in whether there is a difference between parents who stayed in Ukraine and those who went abroad in terms of these indicators.

Does this difference exist? What did the survey actually show: stay or go, which decision was better?

The survey involved mostly mothers (98%) aged 18-55 who had lived in 22 different regions of Ukraine before the war, a total of 340 parents. Most of them were people who had been in a safer place for more than a month since they were displaced. Also, interestingly, most of the respondents had a fairly high level of satisfaction of basic needs. This was true both for those who stayed in Ukraine and those who went abroad.

What does this mean for us? On the one hand, it indicates that even despite the humanitarian crisis, which was especially intensively reported in the first months of the war, at least for some displaced people in Ukraine, the level of satisfaction of basic needs did not differ from those who left for abroad. This means that there is no clear answer to the question of whether it was better to stay or go. However, on the other hand, it is also important to understand that this survey involved fairly prosperous parents who had access to the Internet, had been in relative safety for more than a month, and had a fairly high level of basic needs satisfaction. Parents under more stress rarely participate in mass surveys. Therefore, we should be modest in our conclusions and findings from studies of similar design, and understand that they do not represent the experience of the entire group of parents.

The study also found that living abroad allowed children to have better access to education, which is understandable given the precarious situation with children's education in Ukraine, especially in the first months after the full-scale invasion. Parents who were displaced abroad reported higher chances of being employed (the latter especially affects the ability of parents to better manage their emotions). However, at the time of the survey, many parents from both groups were still unemployed (51% in Ukraine and 41% abroad).

And who coped better with emotions where parents were calmer: in Ukraine or abroad?

According to our data, regardless of whether parents stayed in Ukraine or moved abroad, they used both more positive and more negative strategies to regulate their emotions. In particular, on the one hand, they resorted to short-term planning and putting the situation in perspective, which means focusing on solving current issues that they have influence over and realizing that this situation could be worse, that there are other people who have a harder time. However, on the other hand, the tendency to rumination - excessive focus on one's own negative thoughts and experiences - was also quite common. And although parents who moved abroad more often used strategies of positive reassessment and putting the situation in perspective, they also more often reported a lack of purposeful behavior in distress.

What do these results indicate? Probably, they are actually about the "emotional swings" that we have been experiencing and observing in many people since the beginning of the war. When one day you seem to be coping well, you know what to do and how to do it, and your emotions help you do it, and the next day you feel confused and overwhelmed by negative feelings. In the context of mental health, this means that we are at a certain crossroads mentally. One road leads to the restoration of vital activity, and the other leads to mental health problems. And a lot depends on the situation that unfolds further. If we go back to the experience of displaced parents, it depends on how well they manage to adapt to life in a new place: learn the language, the rules of coexistence in a new community, find a job, friends, and feel involved in a new place.

Meeting basic needs can be considered an important factor in the emotional regulation of parents. However, as I mentioned above, we should be very modest in our conclusions and understand that they most likely represent the most successful experience of adaptation to the conditions of displacement, either within Ukraine or abroad.

Where were the results made public and why are they important to the world?

The results of our research were presented at several international conferences, including a conference in Milan, where, despite the existence of several sections on Ukraine, we were the only ones representing our country. That's why I emphasize the importance of the presence of Ukrainian narratives at such events. Because, you see, it is not right that the experience of Ukrainians is mostly told by foreigners.

That is why we are happy to talk about our research on various occasions, as well as the fact that our article was published in an international scientometric publication. And now it can be consulted by scholars or simply readers who are interested in the experience of Ukrainians in this war, because publications in such journals are more trusted, more often and more willingly cited, referenced, and disseminated.